No.103 - Interview with Liberal Arts Communicator KUDO Sakura

Liberal Arts Communicator KUDO Sakura

(National Museum of Ethnology)

What led to your interest in Nepal?

It probably all began with a class I took as a freshman at university. The professor, who later became my mentor, was a cultural anthropologist and specialist in India. Many of her students were very active, and there was an independently organized book club that met fortnightly where interested members would read a book on a selected theme, summarize it, and give a presentation. With the people I met through this group, I traveled to India, and the trip eventually led me to choose Nepal as the subject of my research.

Before the trip, I read extensively to expand my understanding of India. But when we arrived, the inner workings of local households and many other aspects were not readily visible. We were just guests trailing our professor like tourists, and could not observe the realities of local life. This frustration prompted me to book a bus from India and travel right into Nepal. The year was 2006, and the timing was less than ideal because of the Nepalese Civil War then going on.

What inspired you to study the cultural resources of Nepal?

In 2006, Nepal was at the tail end of the civil war between government forces and the Maoist faction of the Communist Party of Nepal. The conflict was greatest in the capital city of Kathmandu at that time. Paying little attention to my mentor’s warning, I went to Nepal upon learning that many were getting there via India. Once I reached Kathmandu, I experienced the country’s turmoil firsthand. People would tell me not to go outside as curfews were imposed at various locations and the violence was palpable when I visited the downtown area. On the day of my departure, I saw vehicles burning and a strike going on at the bus terminal.

After returning safely to Japan, I turned to books to try to understand what I had witnessed, in the process of which I began to feel guilty for my previous ignorance. I learned that at that time, Nepal’s civil war had spread to urban areas, significantly affecting not only the country’s political sphere but also the lives of ordinary people. I began to want to be a responsible observer who really understood the country, and that led me to pursue scholarly research as a way to engage with Nepal.

Home of the Himalayas, Nepal is a popular destination for mountain climbing, and the activity is one of the significant tourist attractions for visitors from Japan. I frequently meet Japanese people in Nepal, many of whom are elders either volunteering or traveling. What bothered me was that a significant number of them would express the need to do something about the “poor and pitiful” conditions there. I, in contrast, did not see the local people as impoverished; I wondered why visitors failed to pay attention to the richness of Nepalese culture. The motivation behind my academic pursuit, therefore, is to become a person who can communicate the vibrant culture of Nepal.

What is the attraction of your research to you?

One of the many fascinating aspects of Nepal is its class society. The image of established castes is often seen negatively, but as a social system deeply intertwined with traditional festivals, occupations, and daily life activities it does form the foundations of the social order. The first caste group I was drawn to specializes in fermentation mold production for making alcoholic beverages. Though unthinkable in India’s caste system, the Newar people of Nepal, who are my research subjects, are alcohol-consuming Hindus and Buddhists. According to the 2021 census, they account for approximately 1.3 million people or 4.6 percent of the entire Nepalese population, and many of them reside in the Kathmandu Basin. Alcohol production plays a crucial role in festivals, rites of passage, weddings, and funerals that take place all year round. The variety of castes relating to such events and the division of their roles presents a diverse cultural landscape that makes for quite intriguing research.

A fascinating aspect of my research is that each visit to Nepal presents a new topic for me to explore and understand, and progressively the relationships I have maintained since my first trip have been reshaped. While I remain an outsider who now shuttles between Nepal and Japan, the relationship with my informants gradually changes as I continue to engage with their life events, such as the passing of a father, a son’s coming-of-age ritual, and wedding ceremonies. My own transition from just an outsider into a person close to the family has been quite interesting. My informants now call me pupu (maternal aunt); someone with whom they can talk openly about any topic. I can spend time and interact with them, yet remain generally detached from monetary or parental duties. We have an interesting relationship, one that is not based on kinship. Now I have a clear insight into family affairs and a new perspective on the dynamic between the family and the community, in the context of local events. It’s rather difficult to describe, but my ever-changing involvement with the people I know there is part of the attraction of my research.

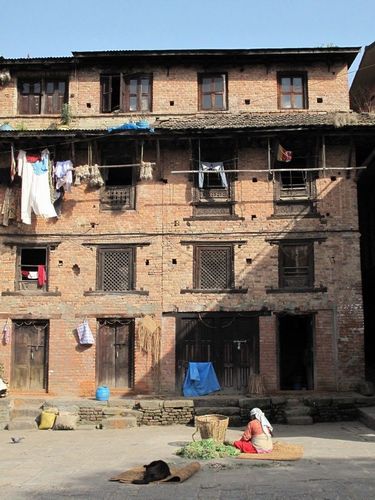

A traditional four-story Newari house. The number of these structures has been declining since the Gorkha Earthquake in 2015.

What are the challenges and difficulties of your research?

Anthropologists like me enter the field armed with a commitment to our research and an objective in mind. Our informants inevitably face emotional experiences or milestone events, but whereas we are in search of research material, they interact with us simply as another person or a foreigner in their lives; most of them are unaware that our exchanges could end up in academic theses and publications. Here lies a common predicament of anthropologists—the struggle to engage with people in the field while having the ulterior motive of finding interesting subject matter.

When scholars lose a particularly close acquaintance in their field, they would usually feel compelled to write a thesis about it. They would present the ways in which relevant rituals were performed, the extent of changes identified from a modern societal perspective, and how the rituals are contextualized within the local society. But I must confess that I cannot distance myself from the grief of such a loss. Technically, I could write an academic paper with the permission of the bereaved family. But I would be emotionally affected if I lost a person with whom I have interacted. As a person who puts priority on sharing emotions, I take extra caution in my writing. I agonize over how to approach a subject, because I want to avoid exploiting any situation just for my academic benefit. These days, even if I write my thesis in Japanese, the people in the field can find and read it online. This has drastically changed the sense of responsibility that researchers have in this regard.

To master the Nepali language, I took a temporary leave from my master’s program and spent about nine months in Nepal. I routinely visited a tea shop frequented by interpreter guides with a high level of language proficiency. Every day, I would listen to their conversations, even when they did not pay attention to me. Then, after returning to my lodgings, I would look up in my grammar books the phrases and expressions that I picked up.

But it can be risky for a foreign woman without local language skills to go out alone. Nepalese value interpersonal connections, which means a lone foreign woman outside the community’s network makes for easy prey. Although I am not related by blood, my informants currently include me in their “network” as a family member. This ensures that outsiders stay out of my way; their actions are kept in check by the watchful eye of my quasi-family. This protective behavior is a natural byproduct of interpersonal relationships. But in the early stages of my research into Nepal—when I could not understand the language and lacked protective or close personal relationships—I had to endure many unpleasant experiences. For instance, I was forced to go to places I was not expecting to go, participate in events against my will, or cope with absurd demands. In hindsight, my status as an unmarried woman posed a particular disadvantage in addition to my lack of language proficiency. This is perhaps a common issue for scholars conducting fieldwork, and true in other areas [of the world] as well.

Once I started to pick up the local language, I became capable of intervening when, for example, people were not introducing me to others properly. Then the number of unpleasant incidents started to drop. With adequate language skills, we can establish relationships on our own terms. The language factor is likely a key reason why I can quickly connect with the people I need to associate with.

The Nepali language is vital for conducting research in Nepal today. There is also the ethnic Newari language, which is preferred in the Newari community. But people fluent in Nepali—the country’s official language—are treated with respect. In rural villages, many residents still do not speak Nepali.

In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, I earned a visiting researcher position at the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku) as a Postdoctoral (PD) Research Fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). But for two years, I was unable to conduct the fieldwork I planned at all, which I found frustrating. When I first arrived in Osaka in April 2020 under the government-declared state of emergency, I received a notice requiring visiting researchers to “stay at home and not come to Minpaku.” Over the next two years or so, I was not allowed to enter the museum without advance notice of my visiting date. This was a very tough time for me, as not only did the arrangement make me reluctant to visit Minpaku but it also isolated me from the outside world.

During the pandemic, some scholars used the Internet to conduct their research. I occasionally called Nepal as well, but neither my informants nor I were motivated enough to engage in research. I felt like I was not conducting research at all during those days.

The pandemic renewed my awareness of how much I prefer to directly interact with people through fieldwork, and I certainly appreciate what a privilege it is. I also realized how important it was for me to repeat the cycle of traveling to and entering the field, and then reflecting from a distance after returning home—the trips between Nepal and Japan helped me in digesting my observations.

Tell us what sequence of events led you to become a liberal arts communicator.

As a graduate student, I worked as a facilitator and curator. My tasks included managing the secretariat of an academic conference and running the former “Tohoku University Liberal Arts Salon” gatherings, which offered public lectures. These jobs seemed a perfect match for me, and through them, I gained experience in planning open lectures, working in consultation with the speakers. It was exciting to explore how to manage events while highlighting the specialized nature of the lectures, and that experience is one of the reasons why I thought I could become a liberal arts communicator.

When Tohoku University became the host of the International Association for Comparative Mythology’s conference in 2018, I was tasked with assisting with the management of the secretariat for the event. The head of the secretariat wanted to do more than just host the conference at the university, so I proposed various ideas for expanding its scope. These included holding the opening ceremony at a temple in Sendai on the first day of the conference, and making a map so that participants could get to know the city by walking to the luncheon venue, as well as chartering a bus for an excursion to the areas affected by the March 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. The conference expenses could not cover all these activities, so I obtained grants and tourist brochures from and arranged for and explained about their use to, what is now the Sendai Tourism, Convention, and International Association. These tasks were greatly enjoyable. While specific aspects of the work were pleasant, the highlight for me was connecting people. It was exciting to create a space that fostered interchange; for example, connecting an academic event with a temple, obtaining public funds from an organization not typically associated with a university, and then facilitating interaction among conference participants through their specialties.

The role of liberal arts communicators basically consists of connecting people, and it is predicated on interpersonal ties. Collaborative research projects among researchers are daunting in and of themselves, but our duties involve working not only with scholars but also with professionals with specific expertise to obtain their collaboration. Further, in social outreach projects—such as the one I am currently involved in—we explore ways that Minpaku’s faculty as well as schoolteachers and other people can utilize the various resources of the museum for children. In FY2024, I will be part of a project to consider and suggest higher-education applications of Minpaku’s resources, ranging from video, audio, and specimens to “Min-Pack” educational kits.

My understanding was that liberal arts communicators are people who plan and draw up potentially interesting collaborations, so this sounded like a fulfilling job for me.

Are there any differences in the research environment between a university and an inter-university institute?

At its core, Minpaku is a research institute with a museum function, and the museum is a space to present research results. In this regard, my research activities remain largely unchanged.

The biggest difference in the environment is the absence of faculty offices where students in their seminars can gather casually. My thoughts on this matter are likely influenced by my experience at my alma mater. Tohoku University’s Department of Religious Studies, to which I belonged, has a long history dating back to the school’s predecessor, Tohoku Imperial University. Perhaps because of the institution’s long history, the professors greatly valued vertical relationships. The professors’ seminars are a time-honored tradition through which they cultivate vertical ties with graduate and undergraduate students. Despite occasional challenges—like having to sit through a two-hour lecture about one’s faults—the seminar room environment enables individuals to gain diverse insights from upper-class students and engage in casual research discussions with peers. I discovered how enjoyable it can be to learn from others over a cup of coffee and in a non-formal setting.

Minpaku, by contrast, has only a common room for lounging but not everyone uses it, so at times I find myself missing the seminar rooms of other institutions. Both my mentor at Tohoku University and I believed that trivial conversations could spark ideas. It would be nice if Minpaku’s scholars could talk about their fields in a casual environment as well.

On occasion I would be asked to give a presentation immediately after my return from the field. This made me nervous and anxious, as I was unsure how I should explain my findings and had yet to identify the compelling facets of my findings. These situations made me appreciate the value of open discussion of my observations in a seminar room environment and the opportunity it afforded to objectively review the topics that interested me. This was the attraction of my alma mater professor’s research office-cum-seminar room.

How do you want to approach the role of a liberal arts communicator from here on?

I am not entirely sure yet. At Minpaku, I work as a liberal arts communicator of the Working Group for Social Collaboration Project. One of our jobs is to coordinate with a team of public volunteers—people who are interested in Minpaku and get involved with the museum’s event-management tasks. We also rent out learning packets called Min-Pack to educational institutions such as elementary and junior high schools to help with their educational programs. Minpaku also hosts regular events including ongaku no saijitsu (lit., music holiday) [in which the museum welcomes both amateur and professional musicians to perform using musical instruments from around the world].

We have a fully booked schedule for FY2024, so I probably cannot plan anything new. But I am currently collecting data, aiming to have high school students utilize Minpaku’s resources. This fiscal year, I will take over the museum’s previous internal tasks and analyze data. I will accordingly compile a report to share and suggest example uses of the resources, and present their ultimate educational benefits based on the feedback received.

(Interviewer: OHBA Go, Researcher, Center for Innovative Research, National Institutes for the Humanities)

KUDO Sakura

Project Assistant Professor, National Museum of Ethnology

KUDO obtained a doctoral degree in religious studies from the Department of Human Sciences, Tohoku University Graduate School of Arts and Letters in 2019. She assumed her present position after serving as a project researcher in disaster humanities at Tohoku University’s Center for Northeast Asian Studies, as well as a Postdoctoral (PD) Research Fellowship under a JSPS grant, and as a visiting researcher at Minpaku. She specializes in the anthropology of religion and the study of contemporary Nepal.