No.104 - Interview with Dr. SHIBATANI Masayoshi, the Fifth Winner of the NIHU International Prize in Japanese Studies

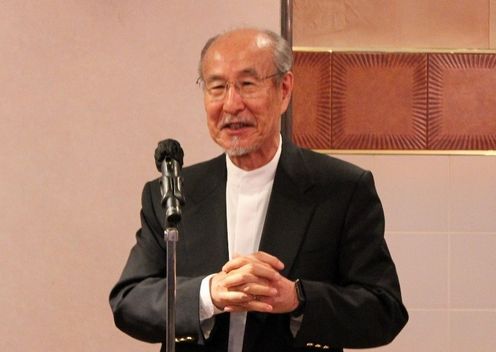

Interview with Deedee McMurtry Chair Professor of Humanities and Professor of Linguistics Emeritus, Rice University and Professor Emeritus, Kobe University Dr. SHIBATANI Masayoshi

Dr. SHIBATANI Masayoshi has spent more than fifty years researching Japanese and general linguistics, linguistic theory, Asian linguistics, and other fields, both in Japan and abroad. On the occasion of his receiving the fifth National Institutes for the Humanities (NIHU) International Prize in Japanese Studies, in this interview, we asked Dr. SHIBATANI about his areas of expertise and the research environment in Japan and the United States, among other topics.

NIHU president KIBE(left), and the fifth winner Dr. SHIBATANI (right)

What led you to study linguistic theory in the United States?

I don’t know why, but I was naturally good at English during my high school years. It was the only subject that I excelled in school and that I kept studying even after I graduated from high school and started working in a private firm, for instance, by taking classes at the YMCA. As you know, mastering English is a major challenge for Japanese, and this prompted me to explore better methods for learning foreign languages. At that time, structural linguistics was mainstream, and some English-language textbooks adopted it. While still living in Japan, I started reading both English and Japanese versions of books written by linguists at the University of Michigan, who had developed what was known as the “Michigan Method.”

I entered the Department of Linguistics at the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) with the hope of discovering methods that would facilitate learning English. However, while the psychology department and the School of Education had faculty interested in language acquisition, the linguistics department focused primarily on linguistic theory and language analysis. As I delved into these areas, I became fascinated and have remained captivated ever since.

The study of language acquisition thrived from late 1970’s through 1990’s but has lost momentum in recent years. This shift is linked to the rise and fall of linguistic theory and highlights the need to advance the theory of language itself to succeed in applied research.

Although applied linguistics fields, such as language acquisition, may appear to have a low barrier to entry, they are actually highly challenging—potentially even more so than purely theoretical studies. Success in these fields demands a deep understanding of both general linguistics and field-specific requirements, including psychology, experimental methods, and other relevant technical skills. I have yet to summon the courage to enter and excel in such a demanding and challenging field.

What is the attraction of theoretical research to you?

It is the joy of gaining a higher perspective on phenomena that have traditionally been analyzed as disparate or unrelated. The essence of theoretical research lies in finding order in a seemingly chaotic world. We struggle to navigate between theoretical ideals—a simple yet comprehensive analysis—and the oft-unyielding nature of data. This process brings both much brain-wracking during problem-solving and incredible satisfaction and pleasure upon achieving a resolution.

Please describe the specific activities and issues of linguistic theory research.

After working out a research question, the next challenge scholars face is to present their findings in a clear and understandable manner, whether through lectures in professional meetings and classroom, as well as, written work. However, everyone has ready-made ideas or assumptions about almost everything, and this complicates academic discourse, classroom instruction, and practical problem-solving. In our field, the grammar taught in schools often instills students with preconceived notions about language. Not only textbooks but also professional writings do the same. However, many of the grammatical "facts" learned in school and academic journals of the highest standard need to be constantly revised or even discarded in light of new discoveries and advancement in the field. This issue also applies to the topics discussed in my commemorative lecture in Tokyo.

For instance, grammatical terms like rentaikei (adnominal/attributive forms) or rentaishi (adnominal words) suggest that rentaikei forms—such as classical Japanese oturu (falling) and kuroki (what is black)—are part of verbal inflection, katsuyo, designed to modify nouns. These forms are indeed used as modifiers, as in examples like (a) [oturu] mizu (falling water) and (b) [kuroki] kokoro (black heart). However, they also appear independently of the modified noun, as in (a') [mizu no oturu] o nagamu (watch the falling of water) and (b') [kuroki] wa hito no kokoro nari (what is black is one’s heart), where there is no nominal (taigen) for the rentaikei forms to modify.

These so-called rentaikei forms are also referred to as kankeisetsu (relative clauses), but this is also misleading given examples such as (a’) and (b’) above, which lack a noun phrase being modified by these "relative clauses." I am currently spending an enormous amount of time and energy to demonstrate that analyzing these forms and structures as rentaikei or relative clauses is fundamentally mistaken. Instead, they should be understood as quasi-nominals or grammatical nominalizations (juntaigen), serving two primary functions: as the main element of a noun phrase (as in a' and b') and as a noun modifier (as in a and b). There are no independent forms/structures like rentaikei or relative clause apart from a modification use of grammatical nominalizations.

As these examples illustrate, grammar is a field where terminology and analysis are continuously subject to reconsideration. Scholars have a responsibility to correct inaccuracies in grammar books based on the findings of theoretical research, which is essential for underpinning these corrective efforts.

Please explain the significance of “identifying the boundaries and properties of possible human languages,” the goal of your research.

This issue is significant on two levels: societal and human. Let me start with the social significance. Data on various languages are crucial for advancing theoretical research on language, which explores human linguistic capacity—what kinds of communication systems can be human languages, and what kinds cannot? Describing and analyzing a vanishing language is profoundly important because losing a language means not only the disappearance of cultural heritage but also a narrower perspective on human linguistic capability. Imagine how distorted our understanding would be if the world spoke only Chinese or Spanish. Approximately 80 to 90 percent of the world’s 6,000 languages are endangered to varying degrees. Many of these languages are expected to vanish within the next 100 years. The causes of language loss are numerous; major factors include the dominance of majority languages and prejudice against minority cultures and their languages.

Japan’s minority languages—peripheral Japanese dialects, as well as the Ainu and Ryūkyūan languages—have historically faced oppression, though less so in recent years. There was a time when people from rural areas of Japan were ashamed of their dialect. People from the Tohoku region, for instance, used to be mocked for their strong accent when they arrived in Tokyo. Hiding or giving up one’s dialect or mother tongue leads to the denial or loss of the speaker’s identity, and this problem is not confined to Japan’s past. Minority populations in areas including North and South America and many parts of Asia face alcoholism, drug abuse, and other contemporary issues attributable to the loss of the language and culture unique to a specific group of people.

In terms of these social issues, linguists’ research efforts can help to restore local ethnolinguistic communities. Through fieldwork—in other words, by visiting the field to collect linguistic materials for research—we can inform local societies the theoretical significance of our findings identified by studying their language. Put another way, linguists can specifically present the positive value of underrepresented languages. This can help community members view their vernacular with pride, attachment, and affection, instead of shame or negativity. Beyond these positive psychological shifts, linguists can support the development of language classes and preparations of textbook, as witnessed in the driving the momentum worldwide to restore and maintain minority languages, such as Ainu and Ryūkyūan in Japan, and the indigenous languages of Native Americans, Indians, and Australians, among others.

Regarding the significance of linguistic research for humanity, our efforts hold the key to answering a crucial question: specifically, how the existence of language distinguishes humans from other animals. On a biological level, chimpanzees and humans are said to be nearly identical, differing only by 1.23 percent in DNA. And yet, humans are vastly different from chimpanzees, with language being an important factor separating us.

Bees also have a considerably sophisticated system of communication, and birds and other animals have dialects as well, similar to those of human language. Still, no animal language has been found yet that allows infinite utterances like those in human language. Investigation into the continuity and disconnect between human language and animal communication systems would directly help us understand the uniqueness of humans as a species.

How different is the research environment between the U.S. and Japan?

After graduating from UC Berkeley, I have had the privilege of teaching at three institutions: the University of Southern California for six years, Kobe University for 23 years, and Rice University for 19 years. This has allowed me experience the educational and research environments of both the United States and Japan. In focusing on the research environment, two key issues emerge: the allocation of faculty and research budgets, and the time available for research.

Unlike Japanese universities, which historically separated faculty into units for liberal arts education (kyoyobu) and specialized disciplines (gakubu), U.S. universities do not maintain this division. Instead, U.S. faculty members are typically organized within specialized departments such as English, Chemistry, or Linguistics. Consequently, even in relatively small fields like linguistics, U.S. departments often have at least seven or eight faculty members. In contrast, Japanese universities, due to the legacy of the kyoyobu-gakubu system, tend to distribute faculty members of the same discipline across different units, resulting in a more fragmented allocation of resources.

Despite this divisive system in Japan, allowing only a handful of faculty members in each discipline in a given school unit, we have been urged to grant a Ph.D. in three years. This was the biggest shock to me, because even in the United States, with its relatively generous faculty allocation, students of the humanities and social sciences—including linguistics—typically spend at least five to six years earning their Ph.D.

Except for faculty positions that are endowed by external funds or of some other special type, faculty of U.S. universities receive support for research funding only to cover the travel expenses to attend annual academic conferences. To fund their research, scholars must usually apply for grants from the National Science Foundation (NSF)—the U.S. equivalent of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS)—or other agencies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In Japanese universities, by contrast, each academic unit has conventionally received research funds for use as operating expenses, making faculty members better funded than their U.S. counterparts. In recent years, however, these operating expenses have been on a gradual decline and universities in Japan are increasingly asking their faculty to turn to JSPS and other external sources for research funding. In that respect, research funding in the two countries is today not so different.

Both NSF and JSPS have a general research acceptance rate of less than 30 percent, so scholars need to have substantial research achievements to secure funding. But the number of hours that scholars can devote to research, a factor directly associated with academic achievement, differs considerably between the United States and Japan. In Japan, I recently heard frequent complaints of a surge in tasks not directly related to research that cut into the time available for research. By contrast, in the United States, conditions under which scholars can set aside time for research have been relatively stable. The unspoken rule for younger faculty of U.S. research universities is to allocate around 50 percent of their time to teaching, 40 percent to research, and the remaining 10 percent to other internal school duties. At Rice University, where I used to work, teaching hours differ between the School of Humanities and the School of Social Sciences. In the former, faculty are responsible for two courses in both fall and spring semesters, five hours per week. In the latter, to which the Linguistics Department belongs, faculty have either one or two courses—a relatively good balance of five hours per week for one semester and two and a half hours per week for the other. Half the courses are graduate-level classes, which are often directly connected to the instructor’s research. The time spent on these classes can often be counted as research hours. Also, unlike in Japan, academics in the United States usually do not work at other institutions as part-time instructors (hijokin koshi).

As for administrative duties, small divisions such as a linguistic department communicate almost exclusively by email, and monthly or semi-monthly faculty meetings end in an hour or two. Other responsibilities include meeting and counseling students on a one-on-one basis and preparing letters of recommendation, but these are manageable tasks.

During the three-month summer vacation (the annual salary of U.S. universities is usually calculated on a nine-month basis), academic staff are not paid, but in exchange, there are no administrative duties. There is also a nearly month-long winter break around Christmas. After six years of teaching, faculty members may take a six- to 12-month paid sabbatical leave as well.

As you can see, teachers at U.S. research universities generally have more time for research throughout the year compared to their peers in Japan. Indeed, dedicating substantial time to research is essential for securing and maintaining a career in American academia. While obtaining a teaching position at a U.S. university may be an initial achievement, the path to tenure—which provides lifetime job security—is highly challenging. The need to overcome these two hurdles fosters intense competition, making adequate time for study crucial for scholars in U.S. academia.

Dr. SHIBATANI delivering his speech.

What is the current situation of the humanities in the U.S.?

I believe the tradition of valuing the humanities has endured over time. During my undergraduate years at Berkeley, we were encouraged to explore various subjects across different disciplines. Friends pursuing careers in medicine, law, and other fields took courses in diverse areas such as linguistics, anthropology, and paleontology. U.S. higher education institutions generally uphold the tradition of promoting liberal arts education at the undergraduate level, while reserving specialized studies for graduate school. However, recent years have seen a growing emphasis on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education, even with U.S. high schools increasingly focusing on these fields. While I recognize the importance of this trend, I am concerned that the potential issues and repercussions of an overemphasis on STEM education, often at the expense of the liberal art education, are not being adequately addressed.

Serious risks could arise if the STEM sector advances without parallel emphasis in ethical, moral, and humanistic values. Active debates are ongoing regarding issues such as artificial intelligence, gene manipulation, and social media, as we seek to establish appropriate regulatory standards and decisions. Humanistic values provide the foundation for making sensible choices. It is crucial to emphasize that as science and technology advance, the role of the humanities becomes ever more important in guiding their development in a responsible direction.

Do you have any message for young scholars and students?

We must always maintain a critical mindset. In other words, don’t simply accept everything a professor says or every scholarly study you read. While a sufficient understanding of previous research is essential, our starting point should be a critical attitude toward what we have been taught and what we read. We must constantly ask ourselves: Can this (additional) data be corroborated by the proposed analysis? Isn’t there a better (simpler but more comprehensive) approach to this problem? A willingness to explore new ideas, rather than merely conforming to or following established views, is crucial for achieving original scholarship. Don’t be afraid to be a loner.

Trust and value your instincts. If a "gut feeling" sparks an idea, you have already accomplished a significant portion of your research. While you may or may not achieve the desired results, the process of proving a seemingly promising idea was wrong after all is as valuable as validating previous studies. This process generates new research, and your instincts will improve with practice.

A gut-feeling hypothesis can be bold and audacious, and that’s perfectly fine. The more radical the idea is, the more effort you need to invest in gathering sufficient data to support your argument. At the same time, listen humbly to what the data tells you, compare it with your hypothesis, and be willing to revise your argument accordingly. Using an approach like this to develop your scholarly inquiry and draw your own conclusions—allowing you to see a new horizon that no one else has seen—is the true satisfaction of theoretical research.

(Interviewer: OHBA Go, Researcher, Center for Innovative Research, National Institutes for the Humanities)