Interview with Liberal Arts Communicator KAWATA Shōko

National Institute of Japanese Literature KAWATA Shōko

I loved picture books as a child and have been fascinated by monogatari, or narrative tales, from when I was young. After we started studying classical Japanese literature (koten) in high school, I slowly began reading classical texts on my own. Thrilled that I could read thousand-year-old tales, I developed an interest in Japanese literature. What was really decisive was my homeroom teacher’s advice to familiarize myself with the story of Tale of Genji—the 11th-century novel by Murasaki Shikibu (ca 973–ca 1014)—in preparation for university entrance exams. So I read YAMATO Waki’s Asaki yumemishi [Shallow Dreams] (Tokyo: Kōdansha, 1980–1993)1. Waki’s series is an adaptation of The Tale of Genji in the format of a shōjo manga, Japanese comics aimed at girls and young women. It incorporates Japanese poetry verbatim from Murasaki Shikibu’s original text, and I was captivated by how the content of the poems ties into the storyline. That led me to study Japanese literature further after entering Tsurumi University’s School of Literature.

During my first and second years, I immersed myself in courses covering Tale of Genji and other Heian period (794–1185) literature. But a class that I took in my junior year on kusazōshi, or fiction published in a picture-book style around the eighteenth century, drew me into the world of Edo-period (1603–1867) literature and prompted me to adopt that as my major in my senior year. The theme of my graduation thesis was the representation of tengu—supernatural beings featured in Japanese folklore—in pre-Edo-period literature and how the depiction changed in literary works from the Edo period and beyond.

As I graduated from university and searched for a job, I reflected deeply on what would bring me happiness in life. The first thing that came to mind was the process of writing my thesis. In hindsight, I realized I was well-suited for and greatly enjoyed the tasks I undertook for writing my thesis, a process called honkoku: examining materials or converting cursive scripts (kuzushi-ji) featured in pre-modern work into modern characters.

With the vague idea of going to graduate school, I consulted with my advisor, who suggested literature from medieval times between the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Azuchi-Momoyama (1568−1600) periods might be a better match for me than that of the Edo period. Following this advice, I changed my major to medieval Japanese literature when I started my master’s program.

1 Available in English as The Tale of Genji: Dreams at Dawn, trans. Stuart Atkin, TOYOZAKI Yōko, and Jennifer Ward, (Tokyo: Kōdansha USA Publishing, 2019–2020).

Since my senior year, I have maintained a curiosity about the people who created and transmitted setsuwa, both orally or in writing, and how and why the tales changed over time.

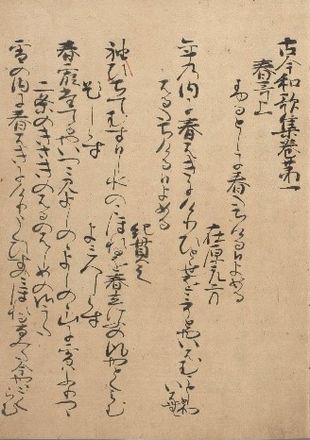

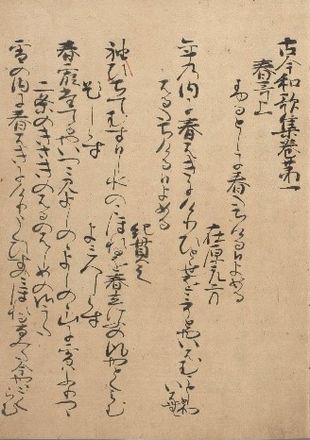

The term setsuwa tends to evoke tales featured in such compilations as Konjaku monogatari shū (Tales of Times Now Past), said to have been compiled sometime around 1120 to 1140. But the term is a general one encompassing myths, legends, and various other tales handed down through oral and written traditions, and is not limited to those compiled in setsuwa collections. Narratives similar to the ones in Konjaku monogatari shū are sometimes cited in commentaries on the poem collections and diaries written by members of the nobility, in which case the meaning ascribed to the tales varies based on the author or editor’s intent. For instance, whereas Konjaku monogatari shū features a certain tale to promote the Buddhist faith, commentary for the circa 905 Kokin wakashū (Collection of Japanese Poems from Ancient and Modern Times) references the same narrative to explain the reason behind the composition of a certain poem. For me, the greatest appeal of setsuwa is such shifts in its ascribed meanings, depending on the person citing the narrative.

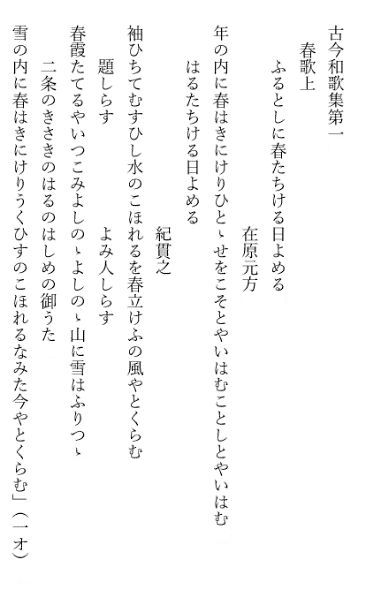

I have never written a thesis in a lateral format, but in my opinion, Chinese poetry and writing (kanshi and kanbun) are easier to cite vertically. Given the strong influence Chinese literature has had on Japanese literature, I cite many sources of Chinese poetry and writing in my theses. From a practical standpoint, a top-to-down orientation is more suitable for the kaeriten marks, used to guide reading of classical Chinese according to Japanese syntax.

Another point is that writing vertically allows faithful reproduction of the character strings in classical works. In the field of Japanese literature, it is common practice to publish materials written in cursive script upon transcribing them into printable characters. In such cases, printing the image of the original material next to the transcription offers greater convenience to the reader than showing just the transcription. The reader can also cross-reference the texts more easily if they are arranged vertically.

Figure 1. Kokin wakashū

(Collection of the National Institute of Japanese Literature;

image from the Union Catalogue Database of Japanese Texts.)

Figure 2. Kawata’s transcription of Kokin wakashū.

The job description on the application guidelines stated that liberal arts communicators “disseminate the results of human cultural research via diverse media including mass communication outlets and collaborative initiatives with the public, such as symposia.” The prospect of working both as a Japanese literature scholar and a curator is what appealed to me the most.

As an undergraduate, I acquired qualification as a curator, and became fascinated with the profession through practical training at the city of Kawasaki’s Japan Open-Air Folk House Museum, where I worked with volunteers to prepare exhibitions and offered brief explanations of the exhibits to visitors. I also worked part-time at Tokyo’s Tobacco and Salt Museum for around seven years as a doctoral student. Through these experiences, I realized the profound significance of a curator’s work, which entails preserving and studying resources and historical materials, and accessibly communicating relevant research results to the general public through exhibitions and other opportunities.

While there had been opportunities to present my research results to scholars at academic conferences and seminars, I had few chances to share my achievements with ordinary people. This is also why I was drawn to liberal arts communicators, as they can convey their research outcomes to scholars and the general public alike.

I find the inter-university institutes an exceptional environment for conducting research. My current research centers on a rather niche subject: commentary developed between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries on the Kokin wakashū. Over 300 works of such commentary are known today, archived at various locations. Previously, scholars had to visit each site in person to conduct their research. But in recent years—particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic—the National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) has increasingly been making images accessible on the Union Catalogue Database of Japanese Texts. This has allowed anyone to search and view online high-resolution images of not only Kokin wakashū commentary but also diverse classical works archived nationwide. NIJL, furthermore, has an extensive collection of prints of classical works that are unavailable on the Union Catalogue Database. Needless to say, it is a risk to conduct research without referencing the primary sources of classical works in person. But I am very grateful that I could use the Union Catalogue Database and the NIJL library to look up which institute has what Kokin wakashū commentary in their archives.

At its core, the inter-university institutes provide scholars of universities and research institutes nationwide with venues for research. NIJL engages in a number of team research projects with academics from such institutes as well. Another of the strengths of the institutes is that they allow one to engage in interchange with various other scholars transcending institutional boundaries.

On the education front, NIJL promotes an undertaking called “Kokubunken de zemi o” (Seminars at NIJL) to promote the utilization of NIJL as a place to host university lectures and seminars. The institute’s library offers direct access to pre-modern Japanese texts, which will likely provide a significant learning experience for undergraduates and others who lack opportunities to view primary sources. These efforts to support universities are one of the important roles of the inter-university institutes.

Universities, by contrast, tend to have a strong student-oriented mindset and focus on how to inform students of research results and processes. As a part-time lecturer currently teaching at my alma mater, I find myself often pondering how I can incorporate certain materials into my classes.

The most recent event I was involved with was the exhibition “Matsuno Bunko no okurimono” (Gift of the MATSUO Yōichi Collection), held at NIJL’s exhibition room from September 5 to October 22, 2024. An archive of books donated by Professor MATSUNO Yōichi, a former director-general of NIJL, the collection primarily features books on Japanese poetry and includes ninjōbon (late-Edo period fiction) and gōkan (a format of publications for kusazōshi). The exhibit was based on the research results of the “Basic Research on the NIJL MATSUO Yōichi Collection” (Main Researcher: TATENO Fumiaki, Associate Professor, Saitama University), and, with the support of team research members, the organizers successfully made an exhibition leaflet featuring many color-print figures.

I also hosted a cursive script-themed workshop at the Toyama City Public Library. The participants were members of the general public, and after I gave them an overview, they tried their hand at reading old cursive characters.

I want to host an event on transcribing kuzushiji, my favorite subject. I got the idea from the website “Minna de Honkoku” (Transcribing Together), which the National Museum of Japanese History runs with the Earthquake Research Institute of the University of Tokyo and the Kyoto University Kozishin Kenkyūkai (Paleoearthquake Study Group). By signing into the page, anyone can participate in transcribing classical works that are publicly available on the website. When contributors encounter an unidentifiable character, they can either get hints using a cursive script recognition AI or receive comments from others knowledgeable of the character in question. I find this webpage fascinating; it would be exciting to arrange an in-person version of it.

Among the classics are non-literary works as well, such as texts on mathematics, science, law, and economics. I hope to see people from various disciplines develop an interest in pre-modern works.

(Interviewer: OHBA Go, Researcher, Center for Innovative Research, National Institutes for the Humanities)

KAWATA Shōko

Specially Appointed Assistant Professor, National Institute of Japanese Literature

KAWATA holds a doctoral degree in Japanese literature from the Tsurumi University Graduate School of Literature (2023), where she now teaches part-time. She assumed her present position after serving as a project research fellow at the National Institute of Japanese Literature (Academic Material Division, Research Information Center). Her research interests include Japan’s anecdotal literature between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries.